Don’t police informal education

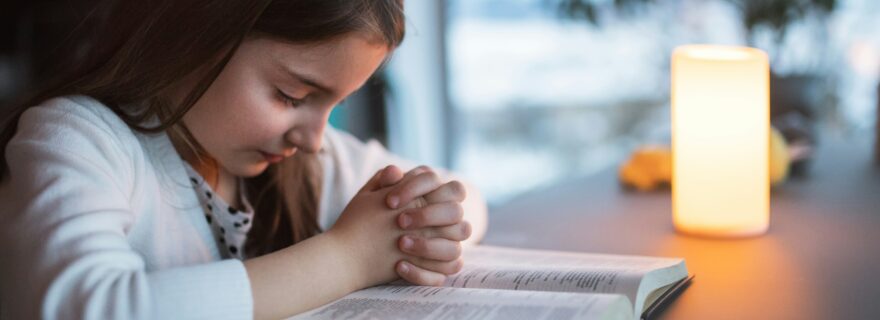

A new proposal to regulate children's informal education in the Netherlands aims to protect them from harmful ideas. But what about their religious freedom?

A new legislative proposal called the Wet toezicht informeel onderwijs (Bill on supervision of informal education), aims to give the Dutch government greater powers to regulate what children learn outside school. This includes weekend schools, tutoring and religious lessons. The goal is to shield children from harmful ideas such as hatred or discrimination. But by focusing solely on protection, the proposal risks overlooking another fundamental right: a child’s right to freedom of religion. The proposed legislation undervalues our rich sources of cultural and religious traditions and the importance of passing them on to future generations of children.

A proposal in political limbo

After the early fall of the Dutch government on the 3rd of June 2025, the House of Representatives reviewed which legislative proposals should be postponed during the caretaker period. The Bill on supervision of informal education is one of these bills. The bill has already been heavily criticised, which might explain the political decision to postpone it. Yet, little attention has been paid to how this bill aligns with the full scope of children's rights as set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). So, a critical legal analysis – and a more holistic reading of the CRC – is all the more necessary.

Informal education under scrutiny

Many children in the Netherlands take part in informal education. For some, these are secular activities, such as homework clubs and community centers. For others, it means Quran school or Sunday school. For this latter group, these spaces can be where they develop values, gain moral orientation, and connect to cultural or religious traditions. However, concerns arise when these places of informal education are suspected of promoting intolerance, exclusion, or anti-democratic sentiments.

This bill gives the Dutch Inspectorate of Education the authority to intervene in informal settings where children may be exposed to messages inciting hatred or discrimination. Although this protective ambition does resonate with key CRC principles, such as the right to be protected from harmful influences (Art. 19) and the right to education that promotes respect for human rights and diversity (Art. 29), the explanatory memorandum’s approach is selective. It cites various CRC provisions related to protection and development, yet Article 14, which guarantees children’s freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, is conspicuously absent.

Why Article 14 CRC cannot be ignored

Children are not mere vulnerable beings in need of protection, they are rights-holders. Article 14 CRC means that a child has the right to freedom of religion independently (i.e. not derived from parents). Article 14 CRC offers an addition to freedom of religion, as it explicitly stated that the child's right to freedom of religion ‘is unambiguously that of the child’. This freedom must be understood in light of the principle of ‘evolving capacities’: as children grow and mature, they become increasingly capable of forming their own convictions and making meaningful choices. Parents may guide, but that guidance must be adapted to the child’s developmental stage.

Importantly, the CRC strictly limits state interference in this domain. Langlaude Doné & Tobin indicate that the bar for governments to limit this right is high and must meet three conditions: it must be necessary in a democratic society, proportionate to a legitimate aim, and the least restrictive means available. The new bill does not meet these requirements, as, by the memorandum’s own admission, inciting messages in informal education are rare.

Overregulation risks undermining trust and rights

Treating all forms of informal education as potentially threatening risks stigmatising entire communities. It may discourage parents from passing on traditions and cast suspicion on cultural or religious identities. Worse still, it may deter children from exploring their values and beliefs.

As the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasised, the evolving autonomy of children should be fostered, not curtailed. Informal education, when inclusive and safe, can support that autonomy. It can help children build moral frameworks, develop critical thinking, and form identities grounded in belonging and reflection, not isolation.

Reframing the debate

The government has a clear duty to protect children from abuse, indoctrination and discrimination. But that duty must be exercised within the framework of international children’s rights law. Any new regulation of informal education must be carefully justified: it should respond to concrete risks, not general suspicion; it must be proportionate, not overreaching; and it must preserve the positive role informal education plays in the development of a child’s identity.

The current bill fails to strike that balance. It views informal education primarily as a threat, rather than as a source of community, meaning and growth. That framing is not only incomplete, it is at odds with a child rights-based vision that sees children as developing individuals with agency, dignity, and voice.

0 Comments

Add a comment