Little Brother is watching you back: Introducing Citizen ‘Protect’

Protect is the new feature launched by Citizen, a controversial crime tracking app, where agents field alerts 24/7 from users in unsafe situations. Is this a new class of digital bodyguards, and at what cost?

To protect and to serve

During the earlier part of this year, Citizen, a smartphone crime-tracking app, began beta-testing their new premium ‘Protect’ service to a group of nearly 100,000 users. Now, for $19.99 a month, all 8 million Citizen users can purchase Protect, which Citizen has advertised as an ‘on-demand, personalized, mobile protection subscription’. Through location-based tracking technology, users have unfettered access to Citizen-employed ‘Protect Agents’. Protect Agents are reachable via audio, video, or text and can help guide users to safety by connecting them to friends, family, emergency service providers, or the police (if need be). Protect mode even comes equipped with a ‘distress detection’ function that can identify human screams.

Citizen’s controversial past

However, questions and concerns have arisen in the aftermath of Protect’s launch. Some doubt the competence of Protect Agents, as job qualifications required for the position are minimal, contrary to Citizen’s claim that its agents are ‘highly trained safety experts’. Others denounce Citizen for creating a privatized 911 service, one that perpetuates and profits from a culture of fear (Furedi, 2002; Mythen & Walklate, 2006).

But Citizen and its founder/CEO Andrew Frame are no strangers to this type of criticism. In 2016, Citizen initially debuted under the name ‘Vigilante’ as a platform where users could report crimes and other incidents in their neighbourhood, typically by submitting photo and/or video footage of an incident in progress. The app’s core function is an interactive, crowd-sourced crime-tracking map. Once an incident has been reported, alerts blast out to users with headlines like ‘Man Fatally Injured’ or ‘Two Vehicles Ablaze on Expressway’. The alert, which includes a geotag and time stamp, then appears as a clickable dot on an interactive map, where users can scroll through live updates and media content. But more inquisitive users are not exclusively limited to the purview of local crime reports, they can also explore the maps of other cities.

As Vigilante gained traction, it also became a hotbed of controversy. Some claimed that the live and fast-paced nature of the app encouraged its users to actively seek out dangerous situations. For this reason (amongst others), police departments condemned Vigilante for interfering with ‘real’ policing. After being publicly blackballed as a virtual forum for emergency voyeurism, Vigilante was banned by the Apple store. But, thanks to some strategic rebranding, the app returned in 2017 with a less polarizing name, Citizen, albeit with the exact same structure and function.

However, Citizen soon found itself embroiled in scandal again, this time related to its harmful potential for digital racial profiling and data privacy issues. As Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst at Electronic Frontier Foundation, explained, ‘the app gives people the power to say who is and who isn't suspicious, and who belongs in their community’ (Gandel, 2021). A particularly poignant example of this occurred earlier this year, when Citizen CEO Andrew Frame seized upon an opportunity to flex Citizen’s ‘policing’ muscle.

In May, a wildfire raged through the Pacific Palisades area of Los Angeles. At Frame’s behest, Citizen users were inundated for hours with frantic alerts, imploring them to help track down the arsonist. They were even offered a $30,000 reward for any information that led to the suspect’s arrest. Eventually, after thousands of tips, a homeless man was detained by the LAPD; however, with no evidence tying him to the crime, he was released. But the damage was already done: an alert containing the name and image of the man had been sent to nearly 850,000 people, falsely identifying him as the arsonist. His image remained on Citizen for 15 hours. A lack of nuanced reporting and frenzied mob justice led to the misidentification and unfounded arrest of an innocent man.

A product of the sousveillant society

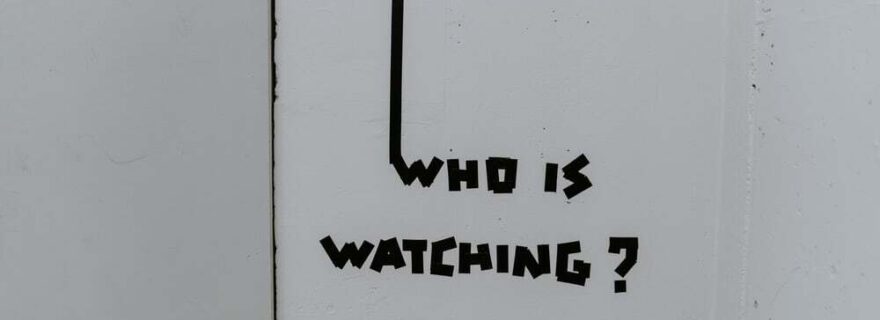

While Citizen and its services may seem like technologies from a dystopic and unfamiliar world, they fit in quite seamlessly with contemporary conceptions of surveillance. As the diffusion of smartphones continues to reach new heights, so too has a different notion of informal social control (Estellés-Arolas, 2020). This concept, sometimes referred to as sousveillance, comes from the French for ‘to watch from below,’ which can be contrasted with the better-known surveillance, meaning ‘to watch from above’. Originally coined by Canadian engineer Steve Mann (2004), sousveillance builds upon existing notions within surveillance discourse to indicate a transition from more formal and hierarchical types of guardianship and responsibility (think here of the Orwellian Big Brother or Bentham’s and, later, Foucault’s Panopticism) to more decentralized and informal types (Ceccato, 2019).

Thus, Citizen takes civilians and enlists them as legitimate purveyors of informal social control. No longer is there merely a downward-looking gaze from sources of power; now, armed with smartphones as ammunition in a sousveillant artillery, ordinary people can watch back and watch each other. Citizen’s Protect service takes this a step further. While Protect doesn’t explicitly claim to be a substitute for 911 or the police, Protect Agents do have the discretion to act as middlemen. And although Citizen does not have formal law enforcement status, it indeed has the capacity to influence policing decisions, as exhibited by the Los Angeles wildfire incident. This marks a striking shift in the relationship between citizens and typical gatekeepers of power.

What does this mean for the letter of the law and those who impose it?

At the moment Citizen is, perhaps, the most visible poster child of crowd-sourced crime-reporting technology, but other apps have and will continue to follow suit. As the boundaries between citizens and State agents begin to fade, lawmakers and law enforcement (amongst other key actors) will have to play a game of cat and mouse to catch up. Indeed, the waters become muddy when citizens are called upon to participate as non-State agents in a domain that almost exclusively belongs to law enforcement. But there is a larger conversation to be had here on notions of accountability, guardianship, and responsibility, which, as Ceccato (2019) suggests, should ‘be explored in ... policing and crime control’.

Should we be excited by or fearful of the sousveillant society and its technological offspring? It seems we can do both, but it is a careful balancing act, one that must be monitored with a critical eye and the knowledge that those who are most vulnerable can and will be negatively impacted.

0 Comments

Add a comment