Undocumented children in limbo

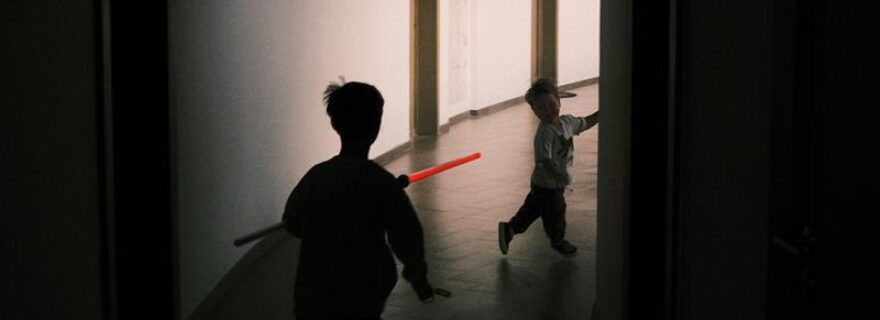

Imagine growing up where you can be fined for playing in the hallway, are moved around all the time, and friends disappear without warning: this is the reality for children in 'gezinslocaties'.

In the Netherlands, many undocumented children live in so-called ‘gezinslocaties’ (GLOs): shelters for families without residence permits who have received an order to leave the country. Families can stay there until they either leave voluntarily or the Dutch government enforces their return.

GLOs were created for humanitarian reasons, but in practice they are sober shelters mainly aimed at encouraging families to leave the Netherlands. That is, the Dutch authorities attempt to ensure that families leave ‘voluntarily’, often through counselling and offering material support after their return. During this process, children attend school, learn Dutch, make friends and effectively ‘integrate' in Dutch society. In contrast, their parents have no access to work and very few possibilities to integrate. Nonetheless, these exclusionary measures do not seem to increase parents’ willingness to leave the Netherlands. Not only that, by interviewing different actors involved in this procedure as well as families living in the GLOs, our research shows that living in a gezinslocatie clearly has a negative impact on their own and their children’s wellbeing.

Daily life inside a 'gezinslocatie'

Residents and support organisations describe GLOs as sober and impersonal. Privacy is limited and there are few safe spaces for children. Some officials say basic needs are met, while conceding that the accommodation is ‘not a 5-star location’. Others even compare GLOs to a ‘summer camp’ for children with plenty of entertainment and friends to play with.

But parents tell a different story. They highlight the hardships their children endure due to continuous uncertainty and the limited material resources available. Typical problems include:

- Little to no access to indoor play areas. In one location, children were fined for playing in the hallways.

- Frequent moves between centres. These disrupt school routines, friendships and stability, causing stress.

- Sudden departures of friends or classmates when the authorities enact forced removals of undocumented families.

Parents argue that these experiences make children insecure in their friendships, and could even lead to depression, burn-out and severe stress.

Additionally, children often have to bear significant responsibilities. Because of their parents’ restricted access to work and limited opportunities to learn Dutch, children involuntarily take on ‘adult roles’. They often support their parents, for instance translating for them when talking to authorities, lawyers, and schools.

Children's rights: what the law says

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), to which the Netherlands is a party, underlines that states may not discriminate against children because of their migration status or their parents’ status. This means that all children on Dutch soil, including those in the GLOs, should have access to the same protection as national children, also when it comes to housing and recreation.

While the Dutch government emphasises their efforts to take children’s interests into account when it comes to legal issues, this seems very limited when it comes to migrant and refugee children including those living in the GLOs. From a legal perspective, many lawyers, government case workers, and support organisations would require better training in how to apply these principles meaningfully. This includes, for example, training on how to speak with children empathetically and ensuring that their voices, rights and ‘best’ interests are considered throughout the asylum process and their living conditions in the Netherlands. Currently, this does not always seem to be the case.

In some GLOs, strong personal networks and committed case workers do make a difference by ‘going the extra mile’ to protect children’s wellbeing. Cross-organisational collaboration seems to be key in achieving this, for example through additional, independent assessments of children’s potential claims for protection. Too often, children are considered an extension of their parents’ claim and do not get to present their own voices and needs. This needs to change in order to systematically focus on the specific needs and rights of children. So far, the inclusion of children’s rights and interests largely depends on the discretion and good will of all actors involved – including government authorities, but also lawyers, judges, teachers, translators and so on.

What needs to change

Children's rights and best interests should be systematically anchored in Dutch law and its practical application in shelters for children. This would help ensure that children’s interests and wellbeing come first in all decisions that concern them, and not primarily in a discretionary manner. Until then, every actor involved – from government officials to lawyers, teachers and health professionals – would benefit from proper training on what the best interest of the child effectively entails in their daily practice.

This blog post is based on preliminary research findings from interviews conducted for the authors’ research project: ‘Whose Best Interests? Assessing the tensions between child welfare and restrictive migration law in gezinslocaties in the Netherlands’. This research is funded by the LDE-GMD Seed Fund 2024-2025. It received the Societal Impact Open and Responsible Science Award from Erasmus University in 2025.

0 Comments

Add a comment