A Tale of Two Democracies

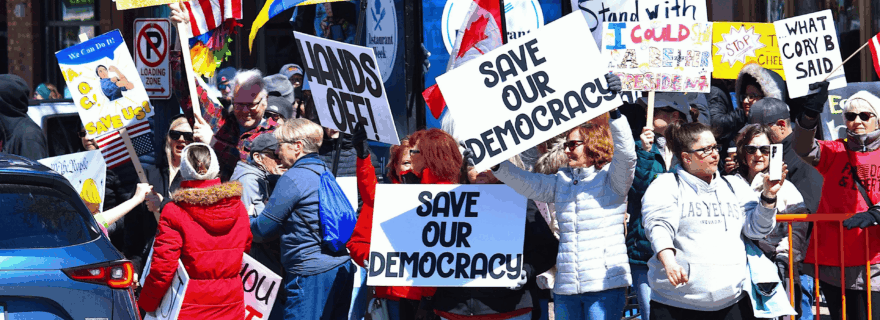

A revolt of the masses – or a revolt of the elites? Democracy has reason to worry about both.

A shared sense of danger

Over the past decade, the sense that democracy and freedom are under threat has become widespread, especially in North America and Europe. There is passionate disagreement, however, about the origin and nature of the threat. On the one hand, many commentators worry about what could be described as ‘a revolt of the masses’. In their view, democracy is being undermined by populist parties, discontented voters and the erosion of constitutional norms, such as judicial independence and the rule of law. On the other hand, however, anti-establishment movements decry what they see as a ‘revolt of the elites’. From this perspective, democracy is being hollowed out by distant elites, technocrats and bureaucracies, who are perceived as bypassing the will of the people to impose their own agendas.

These two fears and visions are often presented as mutually exclusive. Either the people are seen as the danger, or the elite is. Yet this opposition obscures a deeper reality. As my doctoral research argues, both sides are responding to real and potentially dangerous tendencies within modern democracy – and those tendencies are closely connected.

Tocqueville's double warning

Nearly two centuries ago, political philosopher and historian Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) already described this dual danger. Democracy, he argued, is always threatened from at least two sides: by the impulsiveness and passions of the people and by the expansion of centralised power. A society that focuses on only one of these risks can become blind to the other.

Tocqueville famously warned against the ‘tyranny of the majority’, and how the passions and impulses of the majority can be detrimental to the rule of law, to minorities, and to long-term judgement. This concern resonates strongly with contemporary fears about populism. But Tocqueville was equally worried about a more subtle development: the growth of an administrative state that gradually relieves citizens of responsibility while steadily concentrating power at the centre.

Democracy, in short, can decay through too much popular power – when majorities rule without any institutional and legal restraint – but also through too little popular self-government.

Bureaucratic dysfunction and populist backlash

This perspective helps explain why both camps feel besieged at the same time. Modern democracies increasingly respond to social conflict, risk, and inequality by expanding regulation, expertise, and centralised control. The intention is often protective and benevolent. Yet Tocqueville already foresaw that this dynamic can have a paradoxical effect.

Recent research by Olivier Borraz, professor in sociology and Director of Research at Sciences Po, describes this process as a cycle of bureaucratic dysfunction: declining trust in the people’s ability to govern themselves leads elites to centralise more power and limit civil rights (often by proclaiming a ‘crisis’), which in turn deepens resentment among citizens and fuels anti-establishment movements. The result is not more order and stability, but escalation.

From this perspective, populism is not merely a cause of democratic decline; it is also a symptom. When citizens are excluded from meaningful self-government, resentment toward ‘the system’ becomes easier to mobilise – and harder to contain.

Malesherbes' heroic resistance

Tocqueville’s admiration for his great-grandfather, the renowned statesman and attorney Guillaume-Chrétien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes (1721-1794), captures the balance democracy requires. Malesherbes first dared – in what has been called ‘one of the boldest documents ever written’ – to confront royal authority in his Remontrances, defending civil and political freedoms against the centralised power of the king’s government. Twenty years later, during the French Revolution, he courageously offered his legal services and stood by the king as his attorney, this time against the excesses of the revolting masses. A decision for which he ended up paying with his life.

These two heroic moments in the public life of Malesherbes reveal a deeper principle. Genuine commitment to liberty requires resisting any form of unchecked power – whether it comes from above or below. Democratic freedom, in Tocqueville’s view, depends on this difficult posture of dual vigilance.

The art of freedom

Both anti-establishment movements and elites are right to worry about democracy. But they are mistaken when they assume that their anxiety is the only legitimate one. Tocqueville’s enduring lesson is that freedom depends on balance: between leadership and self-government, expertise and participation, elitism and populism.

Freedom does not endure by silencing either side, but by sustaining the tension between them. Learning to live with that tension is what constitutes the art of freedom.

0 Comments

Add a comment